Automatic Music Generation: Difference between revisions

| (7 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 114: | Line 114: | ||

Delete the first element and pass as an input for the next iteration | Delete the first element and pass as an input for the next iteration | ||

Repeat steps 2 and 4 for a certain number of iterations | Repeat steps 2 and 4 for a certain number of iterations | ||

= Understanding the WaveNet Architecture = | = Understanding the WaveNet Architecture = | ||

The building blocks of WaveNet are Causal Dilated 1D Convolution layers. Let us first understand the importance of the related concepts. | The building blocks of WaveNet are Causal Dilated 1D Convolution layers. Let us first understand the importance of the related concepts. | ||

= Why and What is a Convolution? = | = Why and What is a Convolution? = | ||

| Line 127: | Line 124: | ||

For example, in the case of image processing, convolving the image with a filter gives us a feature map. | For example, in the case of image processing, convolving the image with a filter gives us a feature map. | ||

[[File:Conv output.jpg|thumb|alt=In the case of image processing, convolving the image with a filter gives us a feature map|In the case of image processing, convolving the image with a filter gives us a feature map]] | |||

Convolution is a mathematical operation that combines 2 functions. In the case of image processing, convolution is a linear combination of certain parts of an image with the kernel. | Convolution is a mathematical operation that combines 2 functions. In the case of image processing, convolution is a linear combination of certain parts of an image with the kernel. | ||

| Line 136: | Line 133: | ||

convolution | convolution | ||

= 1D Convolution = | |||

The objective of 1D convolution is similar to the Long Short Term Memory model. It is used to solve similar tasks to those of LSTM. In 1D convolution, a kernel or a filter moves along only one direction: | The objective of 1D convolution is similar to the Long Short Term Memory model. It is used to solve similar tasks to those of LSTM. In 1D convolution, a kernel or a filter moves along only one direction: | ||

convolution | [[File:Calculations-involved-in-a-1D-convolution-operation-300x212.png|thumb|alt=Calculations involved in a 1D convolution operation|Calculations involved in a 1D convolution operation]] | ||

The output of convolution depends upon the size of the kernel, input shape, type of padding, and stride. Now, I will walk you through different types of padding for understanding the importance of using Dilated Causal 1D Convolution layers. | The output of convolution depends upon the size of the kernel, input shape, type of padding, and stride. Now, I will walk you through different types of padding for understanding the importance of using Dilated Causal 1D Convolution layers. | ||

When we set the padding valid, the input and output sequences vary in length. The length of an output is less than an input: | When we set the padding valid, the input and output sequences vary in length. The length of an output is less than an input: | ||

[[File:Conv-valid.jpg|thumb|alt=When we set the padding <strong>valid</strong>, the input and output sequences vary in length. The length of an output is less than an input|When we set the padding <strong>valid</strong>, the input and output sequences vary in length. The length of an output is less than an input]] | |||

When we set the padding to same, zeroes are padded on either side of the input sequence to make the length of input and output equal: | When we set the padding to same, zeroes are padded on either side of the input sequence to make the length of input and output equal: | ||

| Line 150: | Line 147: | ||

conv | conv | ||

Pros of 1D Convolution | = Pros of 1D Convolution = | ||

Captures the sequential information present in the input sequence | Captures the sequential information present in the input sequence | ||

| Line 162: | Line 159: | ||

Note: The pros and Cons I mentioned here are specific to this problem. | Note: The pros and Cons I mentioned here are specific to this problem. | ||

= 1D Causal Convolution = | |||

This is defined as convolutions where output at time t is convolved only with elements from time t and earlier in the previous layer. | This is defined as convolutions where output at time t is convolved only with elements from time t and earlier in the previous layer. | ||

| Line 171: | Line 165: | ||

ca | ca | ||

Pros of Causal 1D convolution | = Pros of Causal 1D convolution = | ||

Causal convolution does not take into account the future timesteps which is a criterion for building a Generative model | Causal convolution does not take into account the future timesteps which is a criterion for building a Generative model | ||

| Line 181: | Line 175: | ||

As you can see here, the output is influenced by only 5 inputs. Hence, the Receptive field of the network is 5, which is very low. The receptive field of a network can also be increased by adding kernels of large sizes but keep in mind that the computational complexity increases. | As you can see here, the output is influenced by only 5 inputs. Hence, the Receptive field of the network is 5, which is very low. The receptive field of a network can also be increased by adding kernels of large sizes but keep in mind that the computational complexity increases. | ||

= Dilated 1D Causal Convolution = | |||

A Causal 1D convolution layer with the holes or spaces in between the values of a kernel is known as Dilated 1D convolution. | A Causal 1D convolution layer with the holes or spaces in between the values of a kernel is known as Dilated 1D convolution. | ||

| Line 195: | Line 185: | ||

As you can see here, convolving a 3 * 3 kernel over a 7 * 7 input with dilation rate 2 has a reception field of 5 * 5. | As you can see here, convolving a 3 * 3 kernel over a 7 * 7 input with dilation rate 2 has a reception field of 5 * 5. | ||

Pros of Dilated 1D Causal Convolution | = Pros of Dilated 1D Causal Convolution = | ||

The dilated 1D convolution network increases the receptive field by exponentially increasing the dilation rate at every hidden layer: | The dilated 1D convolution network increases the receptive field by exponentially increasing the dilation rate at every hidden layer: | ||

| Line 209: | Line 199: | ||

wavenet | wavenet | ||

= The Workflow of WaveNet: = | = The Workflow of WaveNet: = | ||

| Line 227: | Line 215: | ||

lstm | lstm | ||

Pros of LSTM | = Pros of LSTM = | ||

Captures the sequential information present in the input sequence | Captures the sequential information present in the input sequence | ||

| Line 235: | Line 223: | ||

Implementation – Automatic Music Generation using Python | = Implementation – Automatic Music Generation using Python = | ||

The wait is over! Let’s develop an end-to-end model for the automatic generation of music. Fire up your Jupyter notebooks or Colab (or whichever IDE you prefer). | The wait is over! Let’s develop an end-to-end model for the automatic generation of music. Fire up your Jupyter notebooks or Colab (or whichever IDE you prefer). | ||

Download the Dataset: | = Download the Dataset: = | ||

I downloaded and combined multiple classical music files of a digital piano from numerous resources. You can download the final dataset from here. | I downloaded and combined multiple classical music files of a digital piano from numerous resources. You can download the final dataset from here. | ||

Import libraries | = Import libraries = | ||

Music 21 is a Python library developed by MIT for understanding music data. MIDI is a standard format for storing music files. MIDI stands for Musical Instrument Digital Interface. MIDI files contain the instructions rather than the actual audio. Hence, it occupies very little memory. That’s why it is usually preferred while transferring files. | Music 21 is a Python library developed by MIT for understanding music data. MIDI is a standard format for storing music files. MIDI stands for Musical Instrument Digital Interface. MIDI files contain the instructions rather than the actual audio. Hence, it occupies very little memory. That’s why it is usually preferred while transferring files. | ||

| Line 251: | Line 239: | ||

Let’s define a function straight away for reading the MIDI files. It returns the array of notes and chords present in the musical file. | Let’s define a function straight away for reading the MIDI files. It returns the array of notes and chords present in the musical file. | ||

#defining function to read MIDI files | <nowiki>#defining function to read MIDI files | ||

def read_midi(file): | def read_midi(file): | ||

| Line 285: | Line 273: | ||

return np.array(notes) | return np.array(notes) | ||

</nowiki> | |||

view rawmusic_1.py hosted with ❤ by GitHub | view rawmusic_1.py hosted with ❤ by GitHub | ||

Now, we will load the MIDI files into our environment | Now, we will load the MIDI files into our environment | ||

#for listing down the file names | <nowiki>#for listing down the file names | ||

import os | import os | ||

| Line 304: | Line 294: | ||

#reading each midi file | #reading each midi file | ||

notes_array = np.array([read_midi(path+i) for i in files]) | notes_array = np.array([read_midi(path+i) for i in files]) | ||

</nowiki> | |||

view rawmusic_2.py hosted with ❤ by GitHub | view rawmusic_2.py hosted with ❤ by GitHub | ||

Understanding the data: | Understanding the data: | ||

| Line 309: | Line 300: | ||

Under this section, we will explore the dataset and understand it in detail. | Under this section, we will explore the dataset and understand it in detail. | ||

<nowiki> | |||

#converting 2D array into 1D array | #converting 2D array into 1D array | ||

notes_ = [element for note_ in notes_array for element in note_] | notes_ = [element for note_ in notes_array for element in note_] | ||

| Line 315: | Line 307: | ||

unique_notes = list(set(notes_)) | unique_notes = list(set(notes_)) | ||

print(len(unique_notes)) | print(len(unique_notes)) | ||

</nowiki> | |||

view rawmusic_3.py hosted with ❤ by GitHub | view rawmusic_3.py hosted with ❤ by GitHub | ||

Output: 304 | Output: 304 | ||

As you can see here, no. of unique notes is 304. Now, let us see the distribution of the notes. | As you can see here, no. of unique notes is 304. Now, let us see the distribution of the notes. | ||

<nowiki> | |||

#importing library | #importing library | ||

from collections import Counter | from collections import Counter | ||

| Line 337: | Line 330: | ||

#plot | #plot | ||

plt.hist(no) | plt.hist(no) | ||

</nowiki> | |||

view rawmusic_4.py hosted with ❤ by GitHub | view rawmusic_4.py hosted with ❤ by GitHub | ||

Output: | =Output: = | ||

music generation | music generation | ||

From the above plot, we can infer that most of the notes have a very low frequency. So, let us keep the top frequent notes and ignore the low-frequency ones. Here, I am defining the threshold as 50. Nevertheless, the parameter can be changed. | From the above plot, we can infer that most of the notes have a very low frequency. So, let us keep the top frequent notes and ignore the low-frequency ones. Here, I am defining the threshold as 50. Nevertheless, the parameter can be changed. | ||

frequent_notes = [note_ for note_, count in freq.items() if count>=50] | <nowiki>frequent_notes = [note_ for note_, count in freq.items() if count>=50] | ||

print(len(frequent_notes)) | print(len(frequent_notes)) | ||

Output: 167 | Output: 167 | ||

| Line 364: | Line 356: | ||

new_music = np.array(new_music) | new_music = np.array(new_music) | ||

</nowiki> | |||

view rawmusic_5.py hosted with ❤ by GitHub | view rawmusic_5.py hosted with ❤ by GitHub | ||

Preparing Data | = Preparing Data = | ||

Preparing the input and output sequences as mentioned in the article: | Preparing the input and output sequences as mentioned in the article: | ||

no_of_timesteps = 32 | <nowiki>no_of_timesteps = 32 | ||

x = [] | x = [] | ||

y = [] | y = [] | ||

| Line 385: | Line 378: | ||

x=np.array(x) | x=np.array(x) | ||

y=np.array(y) | y=np.array(y) | ||

</nowiki> | |||

view rawmusic_6.py hosted with ❤ by GitHub | view rawmusic_6.py hosted with ❤ by GitHub | ||

| Line 390: | Line 384: | ||

Now, we will assign a unique integer to every note: | Now, we will assign a unique integer to every note: | ||

unique_x = list(set(x.ravel())) | <nowiki>unique_x = list(set(x.ravel())) | ||

x_note_to_int = dict((note_, number) for number, note_ in enumerate(unique_x)) | x_note_to_int = dict((note_, number) for number, note_ in enumerate(unique_x)) | ||

We will prepare the integer sequences for input data | We will prepare the integer sequences for input data | ||

| Line 404: | Line 398: | ||

x_seq = np.array(x_seq) | x_seq = np.array(x_seq) | ||

</nowiki> | |||

view rawmusic_7.py hosted with ❤ by GitHub | view rawmusic_7.py hosted with ❤ by GitHub | ||

Similarly, prepare the integer sequences for output data as well | Similarly, prepare the integer sequences for output data as well | ||

unique_y = list(set(y)) | <nowiki>unique_y = list(set(y)) | ||

y_note_to_int = dict((note_, number) for number, note_ in enumerate(unique_y)) | y_note_to_int = dict((note_, number) for number, note_ in enumerate(unique_y)) | ||

y_seq=np.array([y_note_to_int[i] for i in y]) | y_seq=np.array([y_note_to_int[i] for i in y]) | ||

| Line 414: | Line 409: | ||

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split | from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split | ||

x_tr, x_val, y_tr, y_val = train_test_split(x_seq,y_seq,test_size=0.2,random_state=0) | x_tr, x_val, y_tr, y_val = train_test_split(x_seq,y_seq,test_size=0.2,random_state=0) | ||

</nowiki> | |||

Model Building | Model Building | ||

I have defined 2 architectures here – WaveNet and LSTM. Please experiment with both the architectures to understand the importance of WaveNet architecture. | I have defined 2 architectures here – WaveNet and LSTM. Please experiment with both the architectures to understand the importance of WaveNet architecture. | ||

def lstm(): | <nowiki>def lstm(): | ||

model = Sequential() | model = Sequential() | ||

model.add(LSTM(128,return_sequences=True)) | model.add(LSTM(128,return_sequences=True)) | ||

| Line 428: | Line 425: | ||

model.compile(loss='sparse_categorical_crossentropy', optimizer='adam') | model.compile(loss='sparse_categorical_crossentropy', optimizer='adam') | ||

return model | return model | ||

</nowiki> | |||

view rawlstm.py hosted with ❤ by GitHub | view rawlstm.py hosted with ❤ by GitHub | ||

| Line 433: | Line 431: | ||

I have simplified the architecture of the WaveNet without adding residual and skip connections since the role of these layers is to improve the faster convergence (and WaveNet takes raw audio wave as input). But in our case, the input would be a set of nodes and chords since we are generating music: | I have simplified the architecture of the WaveNet without adding residual and skip connections since the role of these layers is to improve the faster convergence (and WaveNet takes raw audio wave as input). But in our case, the input would be a set of nodes and chords since we are generating music: | ||

from keras.layers import * | <nowiki>from keras.layers import * | ||

from keras.models import * | from keras.models import * | ||

from keras.callbacks import * | from keras.callbacks import * | ||

| Line 465: | Line 463: | ||

model.summary() | model.summary() | ||

</nowiki> | |||

view raw10_8.py hosted with ❤ by GitHub | view raw10_8.py hosted with ❤ by GitHub | ||

Define the callback to save the best model during training: | Define the callback to save the best model during training: | ||

mc=ModelCheckpoint('best_model.h5', monitor='val_loss', mode='min', save_best_only=True,verbose=1) | <nowiki>mc=ModelCheckpoint('best_model.h5', monitor='val_loss', mode='min', save_best_only=True,verbose=1) | ||

Let’s train the model with a batch size of 128 for 50 epochs: | Let’s train the model with a batch size of 128 for 50 epochs: | ||

| Line 497: | Line 496: | ||

print(predictions) | print(predictions) | ||

</nowiki> | |||

view raw10_9.py hosted with ❤ by GitHub | view raw10_9.py hosted with ❤ by GitHub | ||

Now, we will convert the integers back into the notes. | Now, we will convert the integers back into the notes. | ||

x_int_to_note = dict((number, note_) for number, note_ in enumerate(unique_x)) | <nowiki>x_int_to_note = dict((number, note_) for number, note_ in enumerate(unique_x)) | ||

predicted_notes = [x_int_to_note[i] for i in predictions] | predicted_notes = [x_int_to_note[i] for i in predictions] | ||

The final step is to convert back the predictions into a MIDI file. Let’s define the function to accomplish the task. | The final step is to convert back the predictions into a MIDI file. Let’s define the function to accomplish the task. | ||

| Line 539: | Line 539: | ||

midi_stream = stream.Stream(output_notes) | midi_stream = stream.Stream(output_notes) | ||

midi_stream.write('midi', fp='music.mid') | midi_stream.write('midi', fp='music.mid') | ||

</nowiki> | |||

view raw10_10.py hosted with ❤ by GitHub | view raw10_10.py hosted with ❤ by GitHub | ||

Converting the predictions into a musical file: | Converting the predictions into a musical file: | ||

| Line 546: | Line 547: | ||

Audio Player | Audio Player | ||

Latest revision as of 22:29, 28 August 2021

Overview[edit]

Learn how to develop an end-to-end model for Automatic Music Generation Understand the WaveNet architecture and implement it from scratch using Keras Compare the performance of WaveNet versus Long Short Term Memory for building an Automatic Music Generation model

Table of Contents

What is Automatic Music Generation?

What are the Constituent Elements of Music?

Different Approaches to Music Generation

Using WaveNet Architecture

Using Long Short Term Memory (LSTM)

Implementation – Automatic Music Composition using Python

What is Automatic Music Generation?[edit]

Music is an Art and a Universal language.

I define music as a collection of tones of different frequencies. So, the Automatic Music Generation is a process of composing a short piece of music with minimum human intervention.

automatic music generation

What could be the simplest form of generating music?

It all started by randomly selecting sounds and combining them to form a piece of music. In 1787, Mozart proposed a Dice Game for these random sound selections. He composed nearly 272 tones manually! Then, he selected a tone based on the sum of 2 dice.

automatic music generation

Another interesting idea was to make use of musical grammar to generate music.

Musical Grammar comprehends the knowledge necessary to the just arrangement and combination of musical sounds and to the proper performance of musical compositions – Foundations of Musical Grammar

In the early 1950s, Iannis Xenakis used the concepts of Statistics and Probability to compose music – popularly known as Stochastic Music. He defined music as a sequence of elements (or sounds) that occurs by chance. Hence, he formulated it using stochastic theory. His random selection of elements was strictly dependent on mathematical concepts.

Recently, Deep Learning architectures have become the state of the art for Automatic Music Generation. In this article, I will discuss two different approaches for Automatic Music Composition using WaveNet and LSTM (Long Short Term Memory) architectures.

Note: This article requires a basic understanding of a few deep learning concepts. I recommend going through the below articles:

A Comprehensive Tutorial to learn Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) from Scratch Essentials of Deep Learning: Introduction to Long Short Term Memory (LSTM) Must-Read Tutorial to Learn Sequence Modeling

What are the Constituent Elements of Music?[edit]

Music is essentially composed of Notes and Chords. Let me explain these terms from the perspective of the piano instrument:

Note: The sound produced by a single key is called a note Chords: The sound produced by 2 or more keys simultaneously is called a chord. Generally, most chords contain at least 3 key sounds Octave: A repeated pattern is called an octave. Each octave contains 7 white and 5 black keys

Different Approaches to Automatic Music Generation[edit]

I will discuss two Deep Learning-based architectures in detail for automatically generating music – WaveNet and LSTM. But, why only Deep Learning architectures?

Deep Learning is a field of Machine Learning which is inspired by a neural structure. These networks extract the features automatically from the dataset and are capable of learning any non-linear function. That’s why Neural Networks are called as Universal Functional Approximators.

Hence, Deep Learning models are the state of the art in various fields like Natural Language Processing (NLP), Computer Vision, Speech Synthesis and so on. Let’s see how we can build these models for music composition.

Approach 1: Using WaveNet[edit]

WaveNet is a Deep Learning-based generative model for raw audio developed by Google DeepMind.

The main objective of WaveNet is to generate new samples from the original distribution of the data. Hence, it is known as a Generative Model.

Wavenet is like a language model from NLP.

In a language model, given a sequence of words, the model tries to predict the next word. Similar to a language model, in WaveNet, given a sequence of samples, it tries to predict the next sample.

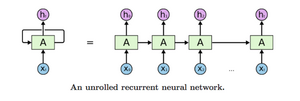

Approach 2: Using Long Short Term Memory (LSTM) Model[edit]

Long Short Term Memory Model, popularly known as LSTM, is a variant of Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) that is capable of capturing the long term dependencies in the input sequence. LSTM has a wide range of applications in Sequence-to-Sequence modeling tasks like Speech Recognition, Text Summarization, Video Classification, and so on.

Let’s discuss in detail how we can train our model using these two approaches.

Wavenet: The Training Phase[edit]

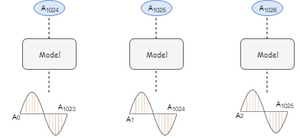

This is a Many-to-One problem where the input is a sequence of amplitude values and the output is the subsequent value.

Let’s see how we can prepare input and output sequences.

Input to the WaveNet[edit]

WaveNet takes the chunk of a raw audio wave as an input. Raw audio wave refers to the representation of a wave in the time series domain.

In the time-series domain, an audio wave is represented in the form of amplitude values which are recorded at different intervals of time:

Output of the WaveNet[edit]

Given the sequence of the amplitude values, WaveNet tries to predict the successive amplitude value.

Let’s understand this with the help of an example. Consider an audio wave of 5 seconds with a sampling rate of 16,000 (that is 16,000 samples per second). Now, we have 80,000 samples recorded at different intervals for 5 seconds. Let’s break the audio into chunks of equal size, say 1024 (which is a hyperparameter).

The below diagram illustrates the input and output sequences for the model:

We can follow a similar procedure for the rest of the chunks.

We can infer from the above that the output of every chunk depends only on the past information ( i.e. previous timesteps) but not on the future timesteps. Hence, this task is known as Autoregressive task and the model is known as an Autoregressive model.

Inference phase[edit]

In the inference phase, we will try to generate new samples. Let’s see how to do that:

Select a random array of sample values as a starting point to model Now, the model outputs the probability distribution over all the samples Choose the value with the maximum probability and append it to an array of samples Delete the first element and pass as an input for the next iteration Repeat steps 2 and 4 for a certain number of iterations

Understanding the WaveNet Architecture[edit]

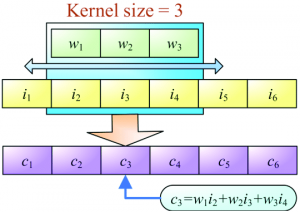

The building blocks of WaveNet are Causal Dilated 1D Convolution layers. Let us first understand the importance of the related concepts.

Why and What is a Convolution?[edit]

One of the main reasons for using convolution is to extract the features from an input.

For example, in the case of image processing, convolving the image with a filter gives us a feature map.

Convolution is a mathematical operation that combines 2 functions. In the case of image processing, convolution is a linear combination of certain parts of an image with the kernel.

You can browse through the below article to read more about convolution:

Architecture of Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) Demystified

convolution

1D Convolution[edit]

The objective of 1D convolution is similar to the Long Short Term Memory model. It is used to solve similar tasks to those of LSTM. In 1D convolution, a kernel or a filter moves along only one direction:

The output of convolution depends upon the size of the kernel, input shape, type of padding, and stride. Now, I will walk you through different types of padding for understanding the importance of using Dilated Causal 1D Convolution layers.

When we set the padding valid, the input and output sequences vary in length. The length of an output is less than an input:

When we set the padding to same, zeroes are padded on either side of the input sequence to make the length of input and output equal:

conv

Pros of 1D Convolution[edit]

Captures the sequential information present in the input sequence Training is much faster compared to GRU or LSTM because of the absence of recurrent connections Cons of 1D Convolution:

When padding is set to the same, output at timestep t is convolved with the previous t-1 and future timesteps t+1 too. Hence, it violates the Autoregressive principle When padding is set to valid, input and output sequences vary in length which is required for computing residual connections (which will be covered later) This clears the way for the Causal Convolution.

Note: The pros and Cons I mentioned here are specific to this problem.

1D Causal Convolution[edit]

This is defined as convolutions where output at time t is convolved only with elements from time t and earlier in the previous layer.

In simpler terms, normal and causal convolutions differ only in padding. In causal convolution, zeroes are added to the left of the input sequence to preserve the principle of autoregressive:

ca

Pros of Causal 1D convolution[edit]

Causal convolution does not take into account the future timesteps which is a criterion for building a Generative model Cons of Causal 1D convolution:

Causal convolution cannot look back into the past or the timesteps that occurred earlier in the sequence. Hence, causal convolution has a very low receptive field. The receptive field of a network refers to the number of inputs influencing an output: causal

As you can see here, the output is influenced by only 5 inputs. Hence, the Receptive field of the network is 5, which is very low. The receptive field of a network can also be increased by adding kernels of large sizes but keep in mind that the computational complexity increases.

Dilated 1D Causal Convolution[edit]

A Causal 1D convolution layer with the holes or spaces in between the values of a kernel is known as Dilated 1D convolution.

The number of spaces to be added is given by the dilation rate. It defines the reception field of a network. A kernel of size k and dilation rate d has d-1 holes in between every value in kernel k.

dilated

As you can see here, convolving a 3 * 3 kernel over a 7 * 7 input with dilation rate 2 has a reception field of 5 * 5.

Pros of Dilated 1D Causal Convolution[edit]

The dilated 1D convolution network increases the receptive field by exponentially increasing the dilation rate at every hidden layer: conv1d

As you can see here, the output is influenced by all the inputs. Hence, the receptive field of the network is 16.

Residual Block of WaveNet:

A building block contains Residual and Skip connections which are just added to speed up the convergence of the model:

wavenet

The Workflow of WaveNet:[edit]

Input is fed into a causal 1D convolution The output is then fed to 2 different dilated 1D convolution layers with sigmoid and tanh activations The element-wise multiplication of 2 different activation values results in a skip connection And the element-wise addition of a skip connection and output of causal 1D results in the residual

Long Short Term Memory (LSTM) Approach

Another approach for automatic music generation is based on the Long Short Term Memory (LSTM) model. The preparation of input and output sequences is similar to WaveNet. At each timestep, an amplitude value is fed into the Long Short Term Memory cell – it then computes the hidden vector and passes it on to the next timesteps.

The current hidden vector at timestep ht is computed based on the current input at and previously hidden vector ht-1. This is how the sequential information is captured in any Recurrent Neural Network:

lstm

Pros of LSTM[edit]

Captures the sequential information present in the input sequence Cons of LSTM:

It consumes a lot of time for training since it processes the inputs sequentially

Implementation – Automatic Music Generation using Python[edit]

The wait is over! Let’s develop an end-to-end model for the automatic generation of music. Fire up your Jupyter notebooks or Colab (or whichever IDE you prefer).

Download the Dataset:[edit]

I downloaded and combined multiple classical music files of a digital piano from numerous resources. You can download the final dataset from here.

Import libraries[edit]

Music 21 is a Python library developed by MIT for understanding music data. MIDI is a standard format for storing music files. MIDI stands for Musical Instrument Digital Interface. MIDI files contain the instructions rather than the actual audio. Hence, it occupies very little memory. That’s why it is usually preferred while transferring files.

- library for understanding music

from music21 import * Reading Musical Files:

Let’s define a function straight away for reading the MIDI files. It returns the array of notes and chords present in the musical file.

#defining function to read MIDI files

def read_midi(file):

print("Loading Music File:",file)

notes=[]

notes_to_parse = None

#parsing a midi file

midi = converter.parse(file)

#grouping based on different instruments

s2 = instrument.partitionByInstrument(midi)

#Looping over all the instruments

for part in s2.parts:

#select elements of only piano

if 'Piano' in str(part):

notes_to_parse = part.recurse()

#finding whether a particular element is note or a chord

for element in notes_to_parse:

#note

if isinstance(element, note.Note):

notes.append(str(element.pitch))

#chord

elif isinstance(element, chord.Chord):

notes.append('.'.join(str(n) for n in element.normalOrder))

return np.array(notes)

view rawmusic_1.py hosted with ❤ by GitHub

Now, we will load the MIDI files into our environment

#for listing down the file names

import os

#Array Processing

import numpy as np

#specify the path

path='schubert/'

#read all the filenames

files=[i for i in os.listdir(path) if i.endswith(".mid")]

#reading each midi file

notes_array = np.array([read_midi(path+i) for i in files])

view rawmusic_2.py hosted with ❤ by GitHub Understanding the data:

Under this section, we will explore the dataset and understand it in detail.

#converting 2D array into 1D array notes_ = [element for note_ in notes_array for element in note_] #No. of unique notes unique_notes = list(set(notes_)) print(len(unique_notes))

view rawmusic_3.py hosted with ❤ by GitHub Output: 304

As you can see here, no. of unique notes is 304. Now, let us see the distribution of the notes.

#importing library from collections import Counter #computing frequency of each note freq = dict(Counter(notes_)) #library for visualiation import matplotlib.pyplot as plt #consider only the frequencies no=[count for _,count in freq.items()] #set the figure size plt.figure(figsize=(5,5)) #plot plt.hist(no)

view rawmusic_4.py hosted with ❤ by GitHub

Output:[edit]

music generation

From the above plot, we can infer that most of the notes have a very low frequency. So, let us keep the top frequent notes and ignore the low-frequency ones. Here, I am defining the threshold as 50. Nevertheless, the parameter can be changed.

frequent_notes = [note_ for note_, count in freq.items() if count>=50]

print(len(frequent_notes))

Output: 167

As you can see here, no. of frequently occurring notes is around 170. Now, let us prepare new musical files which contain only the top frequent notes

new_music=[]

for notes in notes_array:

temp=[]

for note_ in notes:

if note_ in frequent_notes:

temp.append(note_)

new_music.append(temp)

new_music = np.array(new_music)

view rawmusic_5.py hosted with ❤ by GitHub

Preparing Data[edit]

Preparing the input and output sequences as mentioned in the article:

no_of_timesteps = 32

x = []

y = []

for note_ in new_music:

for i in range(0, len(note_) - no_of_timesteps, 1):

#preparing input and output sequences

input_ = note_[i:i + no_of_timesteps]

output = note_[i + no_of_timesteps]

x.append(input_)

y.append(output)

x=np.array(x)

y=np.array(y)

view rawmusic_6.py hosted with ❤ by GitHub

Now, we will assign a unique integer to every note:

unique_x = list(set(x.ravel()))

x_note_to_int = dict((note_, number) for number, note_ in enumerate(unique_x))

We will prepare the integer sequences for input data

#preparing input sequences

x_seq=[]

for i in x:

temp=[]

for j in i:

#assigning unique integer to every note

temp.append(x_note_to_int[j])

x_seq.append(temp)

x_seq = np.array(x_seq)

view rawmusic_7.py hosted with ❤ by GitHub Similarly, prepare the integer sequences for output data as well

unique_y = list(set(y)) y_note_to_int = dict((note_, number) for number, note_ in enumerate(unique_y)) y_seq=np.array([y_note_to_int[i] for i in y]) Let us preserve 80% of the data for training and the rest 20% for the evaluation: from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split x_tr, x_val, y_tr, y_val = train_test_split(x_seq,y_seq,test_size=0.2,random_state=0)

Model Building

I have defined 2 architectures here – WaveNet and LSTM. Please experiment with both the architectures to understand the importance of WaveNet architecture.

def lstm():

model = Sequential()

model.add(LSTM(128,return_sequences=True))

model.add(LSTM(128))

model.add(Dense(256))

model.add(Activation('relu'))

model.add(Dense(n_vocab))

model.add(Activation('softmax'))

model.compile(loss='sparse_categorical_crossentropy', optimizer='adam')

return model

view rawlstm.py hosted with ❤ by GitHub

I have simplified the architecture of the WaveNet without adding residual and skip connections since the role of these layers is to improve the faster convergence (and WaveNet takes raw audio wave as input). But in our case, the input would be a set of nodes and chords since we are generating music:

from keras.layers import *

from keras.models import *

from keras.callbacks import *

import keras.backend as K

K.clear_session()

model = Sequential()

#embedding layer

model.add(Embedding(len(unique_x), 100, input_length=32,trainable=True))

model.add(Conv1D(64,3, padding='causal',activation='relu'))

model.add(Dropout(0.2))

model.add(MaxPool1D(2))

model.add(Conv1D(128,3,activation='relu',dilation_rate=2,padding='causal'))

model.add(Dropout(0.2))

model.add(MaxPool1D(2))

model.add(Conv1D(256,3,activation='relu',dilation_rate=4,padding='causal'))

model.add(Dropout(0.2))

model.add(MaxPool1D(2))

#model.add(Conv1D(256,5,activation='relu'))

model.add(GlobalMaxPool1D())

model.add(Dense(256, activation='relu'))

model.add(Dense(len(unique_y), activation='softmax'))

model.compile(loss='sparse_categorical_crossentropy', optimizer='adam')

model.summary()

view raw10_8.py hosted with ❤ by GitHub Define the callback to save the best model during training:

mc=ModelCheckpoint('best_model.h5', monitor='val_loss', mode='min', save_best_only=True,verbose=1)

Let’s train the model with a batch size of 128 for 50 epochs:

history = model.fit(np.array(x_tr),np.array(y_tr),batch_size=128,epochs=50, validation_data=(np.array(x_val),np.array(y_val)),verbose=1, callbacks=[mc])

Loading the best model:

#loading best model

from keras.models import load_model

model = load_model('best_model.h5')

Its time to compose our own music now. We will follow the steps mentioned under the inference phase for the predictions.

import random

ind = np.random.randint(0,len(x_val)-1)

random_music = x_val[ind]

predictions=[]

for i in range(10):

random_music = random_music.reshape(1,no_of_timesteps)

prob = model.predict(random_music)[0]

y_pred= np.argmax(prob,axis=0)

predictions.append(y_pred)

random_music = np.insert(random_music[0],len(random_music[0]),y_pred)

random_music = random_music[1:]

print(predictions)

view raw10_9.py hosted with ❤ by GitHub Now, we will convert the integers back into the notes.

x_int_to_note = dict((number, note_) for number, note_ in enumerate(unique_x))

predicted_notes = [x_int_to_note[i] for i in predictions]

The final step is to convert back the predictions into a MIDI file. Let’s define the function to accomplish the task.

def convert_to_midi(prediction_output):

offset = 0

output_notes = []

# create note and chord objects based on the values generated by the model

for pattern in prediction_output:

# pattern is a chord

if ('.' in pattern) or pattern.isdigit():

notes_in_chord = pattern.split('.')

notes = []

for current_note in notes_in_chord:

cn=int(current_note)

new_note = note.Note(cn)

new_note.storedInstrument = instrument.Piano()

notes.append(new_note)

new_chord = chord.Chord(notes)

new_chord.offset = offset

output_notes.append(new_chord)

# pattern is a note

else:

new_note = note.Note(pattern)

new_note.offset = offset

new_note.storedInstrument = instrument.Piano()

output_notes.append(new_note)

# increase offset each iteration so that notes do not stack

offset += 1

midi_stream = stream.Stream(output_notes)

midi_stream.write('midi', fp='music.mid')

view raw10_10.py hosted with ❤ by GitHub Converting the predictions into a musical file:

convert_to_midi(predicted_notes) Some of the tunes composed by the model:

Audio Player